Stream Flow: A Tale of Two Rivers

From Rain Fall to River Flow

Water moves in natural cycles. It falls from the sky, it filters through the ground, it travels across the land through rivers to larger bodies of water, it evaporates, and then the process starts all over again.

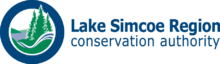

As part of the natural water cycle, rivers play an important role in the health and function of our watershed. When it rains, water moves across the landscape and into the river. Along the way, some of this water is slowed and consumed by vegetation and a portion soaks into the ground to become groundwater. The amount that flows directly into the river is known as event flow.

When urbanization occurs and hardened surfaces such as roads and roof tops replace vegetation, more water flows directly into the river during a rainstorm and makes it there faster. What we see are water flow patterns that change because of urbanization.

Hardened surfaces also prevent water from soaking into the ground to replenish groundwater. Groundwater contributes to the flow in rivers through seeps and upwellings in the river bed. This source of river flow is called baseflow and is what sustains flow in the river between storms and during dry periods. A reduction in groundwater due to hardened surfaces can also result in a reduction in the baseflow of a river.

River Flow into Lake Simcoe

The Lake Simcoe watershed is made up of 35 river and creek systems that annually contribute 10% of the total Lake volume. The map above displays the percent of total river flow each sub-watershed contributes to the lake annually.

Did You Know…

Annual evaporation from Lake Simcoe totals 535 billion litres of water, approximately equal to the total daily flow of Niagara Falls!

Comparing Streams in Different Landscapes

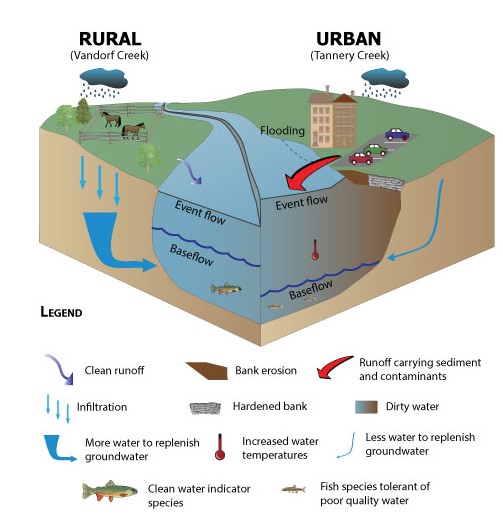

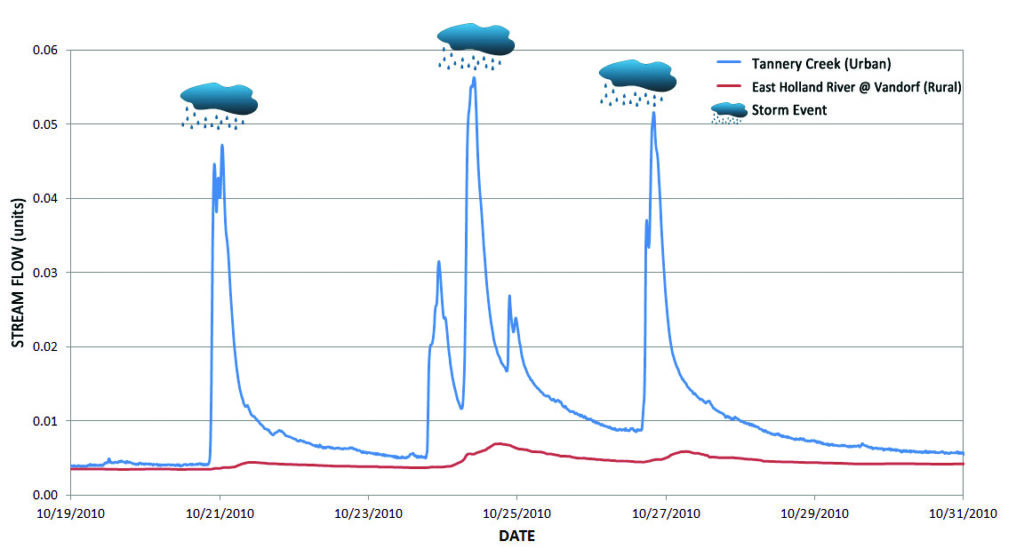

The Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority (LSRCA) measures the change in stream flow resulting from urbanization by comparing how streams respond in different landscapes. Monitoring a stream’s response to rainfall in an urban setting and comparing it to a nearby stream in a rural setting helps us understand the effects of urbanization. An excellent example of this can be seen by comparing the Tannery Creek with its neighbour, the East Holland River at Vandorf Sideroad.

Tannery Creek runs through the most densely populated areas of Aurora and has a slightly smaller watershed. The East Holland River at Vandorf runs through a landscape that is primarily rural. The two areas are located close to each other and typically receive the same amount of rainfall and weather conditions.

Although these two river systems should behave much the same way, this is not the case, primarily because of the increase in hardened surfaces associated with urban areas. Hardened surfaces include things such as roofs, roads and parking lots. These surfaces do not allow water to soak into the ground and instead cause larger volumes of rainwater to move to the river much more quickly.

Comparison of the land use for two reaches of the East Holland River. Tannery Creek is a more urban catchment located to the west, while the East Holland River at Vandorf drains a much more rural catchment to the east

This change is clear when comparing our two study river systems. During and shortly after a rainstorm, the Tannery Creek’s water levels and volume increase dramatically, while the water levels in the East Holland River at Vandorf experience a much smaller response. The larger and higher flow in Tannery Creek impacts the stream banks which are more eroded, have poorer vegetation and murkier water.

In contrast, the banks of the East Holland River at Vandorf are much more stable, have better vegetation, and the water is much clearer.

Event Flow

Stream flow for Tannery Creek and East Holland River at Vandorf showing the different way these two streams respond to similar storms. The urban river (Tannery) has large quick peaks in water flow due to the runoff from hardened surfaces. In contrast the rural river (East Holland at Vandorf) only shows slightly elevated flows due to the greater amount of interception by vegetation and infiltration to groundwater.

Comparing 40 Years of Baseflow in Two Rivers

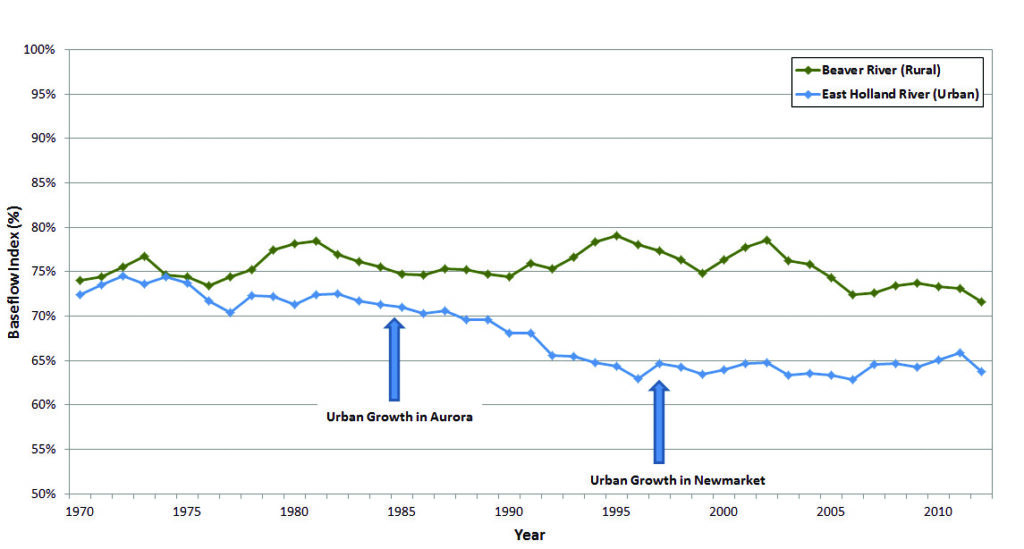

Baseflow Index is a method of comparing the proportion, or percent of baseflow to total stream flow in a stream over a year. Over the long term, changes in the Baseflow Index show how the stream responds to changes such as climate or urbanization.

A comparison of the historical baseflow indices for the Beaver River and East Holland River sub-watersheds illustrates how an increasing urban area can impact the volume of baseflow in a stream.

The East Holland River drains two large urban centres, Newmarket and Aurora. The Beaver River is a primarily rural / agricultural sub-watershed with large wetland areas in the eastern portion of the Lake Simcoe watershed.

In the late 1960s through mid 1970s both subwatersheds had similar baseflow contributions with 5 year average baseflow indices of approximately 75%.

By the late 1980s the baseflow indices for the East Holland River dropped to approximately 70%. This decrease coincided with urban growth in the Town of Aurora that occurred during this same period.

Again in the early 1990s and most notably by 1995, the baseflow indices for the East Holland River dropped again to approximately 65%, here coinciding with increased growth in Newmarket that occurred through the 1990s. In contrast, the Beaver River saw very little urban growth during this period. As a result, the baseflow index remained relatively stable with natural climatic variability having the greatest impact on baseflow.

Baseflow Index of the East Holland River and Beaver River for a 40-year period

The East Holland shows a declining Baseflow Index associated with growth in the urban areas of Aurora and Newmarket. The Beaver River has seen very little increase in urban area and as a result, the Baseflow Index has remained relatively stable.

Why Baseflow is Important

We can see, storm by storm, that an increase in hardened surfaces affects the amount of stormwater running into the river.

By looking at monitoring data over a long period, we can also see how it affects the volume of baseflow in a river. Baseflow is very important for a stream because:

- it helps regulate water temperature which is crucial for many plants and animals,

- it is typically clean and helps to dilute contaminates from runoff,

- it improves water quality and,

- it provides a stable source of water to help augment flow during dryer periods which are typical during late summer or more severely during drought.

A river with good stable baseflow is more resilient to drought and to the anticipated effects of climate change. Unfortunately the increased runoff volume generated by hardened surfaces in urban areas also serves to reduce the amount of water that is able to soak into the ground, replenishing groundwater. As this groundwater is the primary source of baseflow, urbanization can have the added impact of reducing baseflow volumes in streams.

Event Flow = river flow generated by rainfall runoff

Baseflow = river flow generated by groundwater upwellings

Low Impact Development

Low Impact Development (LID) is an approach to managing stormwater that mimics a site’s natural drainage pathways as the land is developed. LID encourages water to seep into the ground to help manage the groundwater and stream levels.

LID principles include preserving natural landscape features, minimizing hard surfaces, and creating drainage systems that treat stormwater as a resource rather than a waste product. In essence, Low Impact Development is about designing spaces that let water travel through its natural cycle as close to the way it did before development took place.

Low Impact Development is not a new concept, but it has not yet been widely adopted in Ontario. At LSRCA, we hope to change this and are working with the development community and government partners to implement LID design into new developments. As well, LSRCA’s “Landowner Environmental Assistance Program” (LEAP) works with municipalities and residents to incorporate LID features into existing properties and businesses.

Low Impact Development involves designing spaces that let water travel through its natural cycle as close to the way it did before development took place.

Reduce Your Water Footprint and Help Your Local Rivers

The old saying that even one person can make a difference still holds true. If you think you are too small to make a difference, try sleeping with a mosquito in the room.

- Anytime you use water outside, try to divert the runoff onto grass or soil. For example, if you wash your car at home, wash it on the grass and not on the driveway. Divert downspouts off driveways and onto your lawn.

- Build a rain garden on your property. Rain gardens help encourage water to collect and slowly seep back into the soil. It means less water in the storm sewers.

- Sweep your driveway to clean it rather than hosing it down.

- Consider alternatives to asphalt for your driveway, such as permeable pavement.

How LSRCA is working to improve the quality of Lake Simcoe

The watershed is a complex and dynamic system, that changes over time in response to both human activities and natural events.

LSRCA works with its many partners, including our communities and municipal, provincial, and federal governments, to protect and restore the environmental health and quality of Lake Simcoe and its watershed. We do this by leading and supporting programs and projects in science and research, protection and restoration, and education and engagement.

Who to Contact:

Customer Service

Phone: 905-895-1281

Toll Free: 1-800-465-0437

Email: info@LSRCA.on.ca

This newsletter was published in Lake Simcoe Living Magazine in 2013.