Lake Simcoe Science

The Phosphorus Cycle

A View From Inside the Lake

Excess phosphorus is the single biggest lake management problem around the world and Lake Simcoe is no exception. In fact, the reduction of phosphorus levels is a key objective behind the provincial government’s Lake Simcoe Protection Act and Plan.

With phosphorus being such a key issue much has been researched and written about its impact on Lake Simcoe. We’ve published numerous reports and studies that explore the issue in detail.

So why another story about phosphorus? So far, the studies we’ve published have focused on our research into how much phosphorus is going into the lake. In this article, we take a look at phosphorus from another perspective – from within the lake itself. In other words, once phosphorus gets into the lake, what happens to it? Where does it go? What does it do?

Did You Know …

LSRCA collects water samples and sediment year-round at 29 lake stations (8 open-water and 21 nearshore) to monitor changes to Lake Simcoe’s health. An additional 142 sites are monitored annually and a further 952 sites are sampled every 5 years.

What is Phosphorus?

Phosphorus is a naturally occurring element essential for all life. It’s found in plants and animals (including humans) and is even found in DNA, the building blocks of all life. It’s also an essential nutrient that supports healthy growth and development. In water bodies such as lakes, a certain amount is necessary, but too much phosphorus fuels excessive plant and algae growth. When the plants and algae die, they consume oxygen from the water, and this has a negative effect on our coldwater fishery.

Phosphorus is a natural element found in plants and animals (including humans). It’s also in products such as cola, fertilizers, toothpaste and shampoo, matches and flares.

We Use Phosphorus Every Day!

Because it’s a naturally occurring element, one source of phosphorus entering the lake is from the weathering of rocks and minerals. And because all life consumes phosphorus, a certain amount is excreted in our waste or released from tissues during decomposition.

Phosphorus is also a very useful element and can be found all around us in many of the products we use, for example in common every day products like cola, fertilizers, toothpaste, shampoo, matches and flares. It is also used in pesticides, pyrotechnics, and the production of steel, to name a few industrial uses.

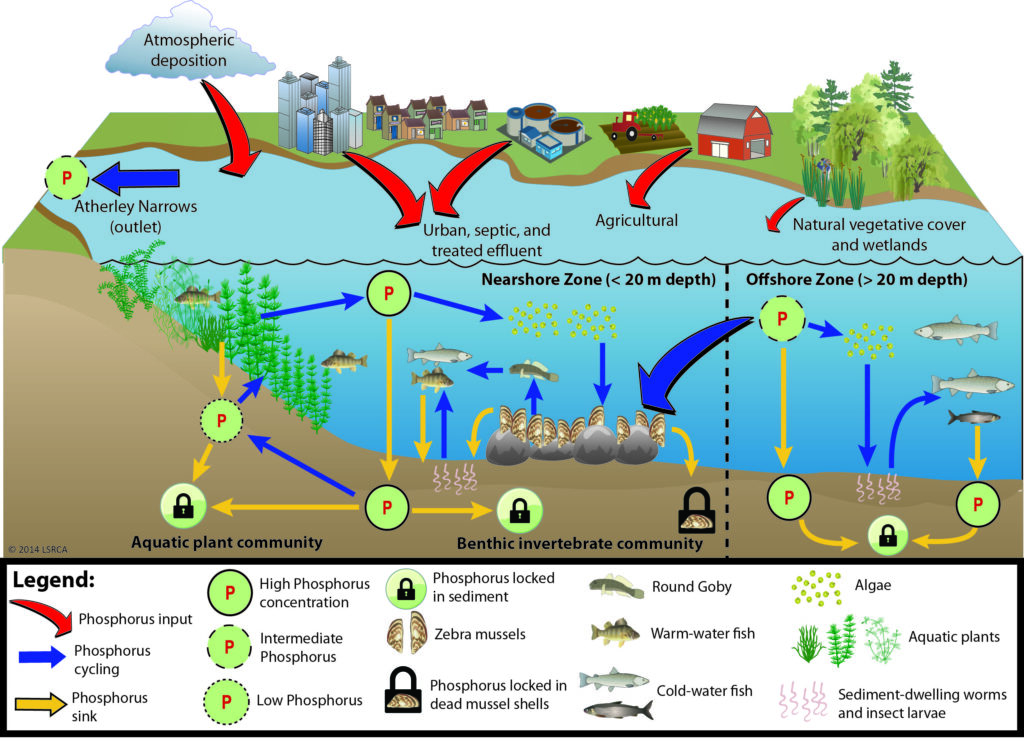

The Phosphorus Cycle

As already mentioned, the phosphorus in the lake isn’t just in the water. It’s also in the plants, the animals and the sediments. All these sources interact, share, store and even lock away phosphorus in what we call the “phosphorus cycle”.

Phosphorus in the Water

The majority of phosphorus that enters the lake is used by all the organisms in the lake or settles out into the sediments. A portion, however, remains dissolved in the waters of the lake. With a lake made up of 11.6 trillion litres of water and an average phosphorus concentration of 14 micrograms per litre, at any given time the lake water will contain approximately 140 tonnes of phosphorus. Target phosphorus concentrations for lake waters are 10 micrograms per litre. Achieving this target, would result in 100 tonnes of phosphorus within the lake.

A certain amount of this dissolved phosphorus leaves the lake each year. Most of this occurs through the outlet at Atherley Narrows where the lake waters drain into Lake Couchiching. Dissolved phosphorus leaving the lake at the Narrows is calculated at an average of 11 tonnes each year.

Concentration of in water total Phosphorus measured since 2008

The size of the circles indicates the average phosphorus concentration at each site, measured in monthly water samples since 2008. All areas have seen improvement since the 1980s when average phosphorus concentration was 20-30 μg/L.

Phosphorus in the Sediment

Phosphorus is also found in lake sediment. Lake wide, the amount of phosphorus within the top 10 cm of sediment is estimated to be 6,200 tonnes. While plants predominately get their phosphorus from sediment, not all sediment phosphorus is accessible to plants. In Lake Simcoe, few plants are found in waters deeper than 10 metres due to the absence of sunlight. The phosphorus in sediment at greater than 10 metres depth is considered a phosphorus “sink”. During periods of low dissolved oxygen however, sediment bound phosphorus can be release back into the water.

Phosphorus deposits in the sediment are not evenly distributed throughout the lake. In a lake-wide survey, LSRCA researchers recorded the locations of high and low concentrations of sediment. In Cook’s Bay, for instance, there is a very low concentration of sediment phosphorus because it is taken up by the large amounts of aquatic plants. In Kempenfelt Bay and near Beaverton, sediment phosphorus is much higher because the plant population is lower.

The Phosphorus Cycle

Phosphorus is constantly being cycled in Lake Simcoe. After flowing into the lake, it is taken up by plants and algae, then cycled to zebra mussels and other invertebrates, as well as fish, then recycled to the water or deposited to sediments.

Phosphorus in the Plants

Two of the main users of phosphorus are plants and algae. In Lake Simcoe, zebra mussels have filtered out the algae. This has resulted in higher water clarity, which allows sunlight to penetrate deeper into the water and encourage abundant plant growth.

Aquatic plants get up to 97% of their phosphorus from lake sediments. When they die, some of the phosphorus in their tissues is released back into the water, while some remains bound in the plant tissue and will be reincorporated into the sediments.

Where these sediments are at a water depth of less than 10 metres deep, the plant tissue phosphorus may be used to fuel plant growth in subsequent years. If the plant material is transported to waters deeper than 10 metres, the phosphorus will become essentially locked away in the sediments.

LSRCA researchers calculated a total mass of 48,000 tonnes of aquatic plants in Lake Simcoe. They studied the three most common species in Lake Simcoe, representing about 75 per cent of the total lake plant mass.

- Muskgrass (9,360 t of plant material)

- Eurasian watermilfoil, an invasive species (10,080 t of plant material)

- Coontail (16,560 t of plant material).

It was determined that, at the peak of their growing season, these three species will absorb 6.3 tonnes of phosphorus out of the sediment and surrounding water. After these plants die and begin to decompose, 2.5 tonnes is recycled back into the water column. The remaining 3.8 tonnes (or 60%) will remain locked in the plant tissues as this material is incorporated into the sediments.

Phosphorus in Zebra Mussels

The zebra mussel, which invaded Lake Simcoe in 1995, has been studied extensively over the past few years. We estimate a lake wide population of 2.9 trillion mussels. Researchers have calculated that 138 tonnes of phosphorus is held in their tissues, a further 9.4 tonnes is held in the shells of living mussels and 29.3 tonnes in shell deposits from dead mussels. While the phosphorus held in the mussel’s tissue will be recycled in the lake system either through predation or decomposition, the 38.7 tonnes held in the shell of mussels is, for all intents and purposes, locked away.

Positive Changes are Happening

The cycle of phosphorus tells us that there are significant reservoirs of phosphorus in Lake Simcoe, and that the lake has many natural processes for assimilating excess phosphorus. When these processes get overwhelmed, the result can manifest in the form of excessive plant growth or algal blooms, indicating a system out of balance.

These reservoirs of phosphorus were caused by many years of excessive inputs. It has taken decades for Lake Simcoe to accumulate this much phosphorus and it will take decades to return to an ecologically sustainable state.

This means that the efforts we make today may not return results immediately, but this doesn’t mean that we should give up or that positive changes are not happening. While the positive results of our work may take some time to be seen or felt, we know the lake is also doing its part and working hard to restore balance. In fact, we are seeing improvements in dissolved oxygen, decreasing phosphorus and the return of some environmentally sensitive species.

What You Can Do

Because a major contributor of phosphorus to the lake is a result of stormwater run-off, there is quite a lot the average person can do:

- Make sure the soaps and detergents you buy are phosphate free.

- When using water outside, direct the excess to the lawn or garden and not through the stormwater system.

- Wash your car at the car wash, where the water will be properly treated. If you must do it yourself, wash your car on the lawn, so that the water soaks into the ground.

- Use native plants in your lawn and garden. They’ve adapted to survive in our climate and therefore don’t have the same need for watering or fertilizer. If you fertilize, look for phosphate free fertilizer.

- Tell others about what you’ve learned and spread the word.

What LSRCA is Doing

Many of LSRCA’s programs are focused on phosphorus reduction.

- We plant trees along streambanks to prevent erosion. This keeps the soil intact, slows water velocity (which reduces erosion), and allows a portion of the water to infiltrate the ground rather than run-off directly into the stream.

- We promote retrofitting stormwater ponds in existing developments to improve water quality. Originally designed to move rainwater away from homes, which addresses water quantity, the link from stormwater ponds to water quality was not as well understood as it is today. Stormwater pond retrofits use innovative technology and are a cost-effective way to reduce the amount of phosphorus from entering the lake.

- We promote low impact development techniques through our RainScaping program, encouraging water in new developments to more closely mimic the natural water cycle.

LSRCA’s environmental projects and programs are funded and implemented in partnership with our communities and municipal, provincial, and federal partners.

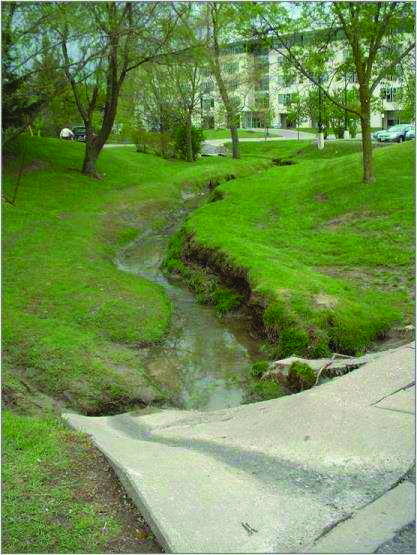

Streambank Restoration

Our stewardship efforts prevent erosion along streambanks to create a naturalized stream channel and fish habitat, allowing a portion of water to infiltrate into the ground rather than run-off directly in the stream.

See an example of streambank naturalization in the before and after photos below:

Who to Contact:

Customer Service

Phone: 905-895-1281

Toll Free: 1-800-465-0437

Email: info@LSRCA.on.ca

This newsletter was published in Lake Simcoe Living Magazine in 2014.